Are we missing something Big in our search for a cure for Cancer? (Part II)

A review of the book, "Tripping over the Truth"

In Part I of this two part series I explained why I am open to the possibility that significant scientific breakthroughs are being ignored (or even suppressed).

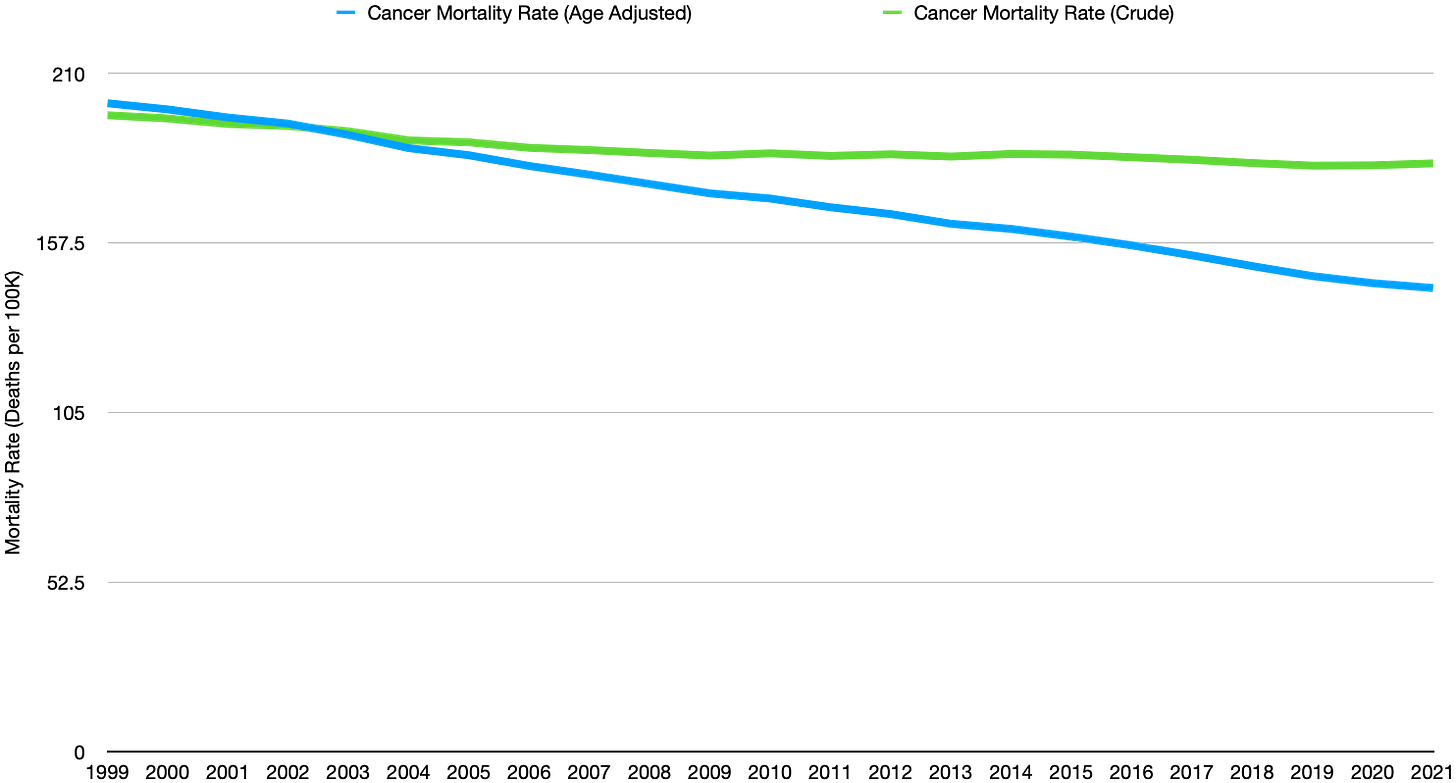

With regard to this topic, cancer, I cited official CDC cancer mortality rates which indicate only meager improvements (see the graph above) despite the staggering (and increasing) expense of oncologic agents.

I asked three oncologists, all of whom I have known for three decades to assess their field. They were all hopeful that more recent breakthroughs in immunologic therapies have finally opened a door leading to discriminate means of combatting cancer. Targeted therapies have brought the field of oncology into a new era.

None expressed frustration around the modest returns on the huge price of oncologic agents to this point in time. Cancer is complicated, has more than one cause and thus a single “cure” will likely never be found.

Between the time I and my oncologist friends finished medical school and 2021 when oncologic pharmaceutical sales were approaching 200 billion dollars per year, overall cancer mortality rates have fallen a mere 8%. Age-adjusted mortality rates, on the other hand, have fallen 28%. In a general sense this means that the risk of dying from cancer isn’t much less, we just are living longer with the disease.

This is certainly a win, but is it worth the expense? Moreover there has been a significant decline in smoking and increased cancer screening for common cancers during this period. How much actual benefit is the 200 billions dollars a year buying the American public?

Given the enormous revenue generated by this class of medicines, is the system incentivized to remain on a path of marginal health returns on massive financial investments?

If it were, how would that look like?

“Tripping Over the Truth”

If you are the kind of person that judges books by their covers, you probably wouldn’t give the book “Tripping over the Truth: How the Metabolic Theory of Cancer is Overturning One of Medicine’s Most Entrenched Paradigms” a second glance. Author Travis Christofferson is not a doctor. None of the glowing blurbs on the back cover are written by medical doctors. Except for one. Dr. Joseph Mercola, who writes:

“Phenomenal…required reading for anyone who has cancer or knows someone who has cancer….I cannot stress its importance enough. Get yourself a copy, and read it.”

Mercola was a practicing Family medicine doc who eventually formed a successful company which promotes “natural” health and “alternative” remedies. Mercola became one of the biggest voices critiquing the Covid pandemic response earning him the top spot on the “Disinformation Dozen”.

He’s a medical pariah. It’s no wonder he’s endorsing a book that seeks to overturn an entrenched paradigm.

However it was Thomas Seyfried, PhD, a professor of Biology at Boston University who also lauded the book who captured my attention:

“The information presented in Tripping over the Truth will have profound consequences for how cancer is managed and prevented”

I had already been aware of a paper Seyfreid authored in 2015, “Cancer as a mitochondrial metabolic disease” published in Frontiers in Cell and Development Biology in which he summarizes a number of elegant experiments conducted by various scientists since 1948 in a variety of animal cell lines which all found something remarkable. When the nuclei of cancer cells were transplanted into normal cells, the new hybrid cell remained healthy.

The implication of this finding should be revelatory. If cancer resulted from defective genes, the hybrid cells should have become cancerous. They didn’t. Something in the healthy cytoplasm prevented whatever genetic cancerous predisposition which existed in the nucleus from manifesting.

Complementary to this finding, authors of this paper, “Cytoplasmic mediation of malignancy” (1988) reported that when a normal nucleus is transplanted into the cytoplasm of a cancerous cell, the hybrid cell remains cancerous 97% of the time.

These basic laboratory experiments clearly demonstrate that the problem is in the cytoplasm of the cell, not the nucleus where our genes reside. Why then have we been targeting processes in the nucleus for all these decades? Could this be the reason we have made only modest gains while a few people thinking outside the box have made breakthroughs?

This is the question Travis Christofferson explores in his book, “Tripping over the Truth”.

How Cancer became known as a Genetic Disease

The National Cancer Institute states:

“Cancer is a genetic disease—that is, it is caused by changes to genes that control the way our cells function, especially how they grow and divide.”

Despite the National Cancer Institute’s dispositive statement that Cancer is a genetic disease, the idea that our genes are responsible for cancer is a theory, known as the Somatic Mutation Theory (SMT). What is the evidence that supports this theory? This is where the book begins.

Christofferson did an admirable job weaving complicated biochemical processes, personal stories of key contributors and the significance of their achievements into a novel accessible to the lay person.

In this essay I will highlight only a few of the most salient story lines he explores. He appropriately begins with explaining how the National Cancer Institute came to their conclusion.

There was the English surgeon, Percivall Pott, who recognized in the eighteenth century that an epidemic of cancerous growths on the scrota of chimney sweeping adolescent boys was likely due to their constant exposure to something in the chimney soot. Cancer, at least in these cases, was due to exposure to something in the environment, i.e. a carcinogen.

Then there was Rudolf Virchow, the “father of modern pathology”, who identified one of the hallmarks of cancer: unregulated cellular division. His student, David Paul Hansemann, noticed something unusual about cancerous cells prior to their division: the newly discovered thread-like objects inside the nucleus called chromosomes did not line up in an orderly fashion like in healthy cells but were chaotically arranged. At that time nobody knew what these chromosomes were and the secrets they contained.

Prior to WWII, cancer treatment was limited to surgery and radiation therapy. The birth of chemotherapeutic oncology began when it was discovered that allied soldiers exposed to mustard gas had a marked depletion of white blood cells in their bone marrow and lymph tissues. This led to experiments with mustine (a variant of nitrogen mustard gas) on patients with non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma which demonstrated that it could shrink tumors.

Other agents like methotrexate, vincristine and mercaptopurine were soon discovered and trialed in limited scopes. All acted through mechanisms that interfered with an aspect of DNA synthesis or cell replication. All had short lived “success”. All were associated with toxic side effects because of their indiscriminate attack on all cells, not just cancerous ones.

Nevertheless their discovery heralded a new chapter in our fight against cancer. We were starting to build an arsenal of chemotherapeutic agents which all targeted DNA. Though these early agents had limited utility because of their toxic profile, their ability to temporarily halt the progression of the disease reinforced the idea that the fundamental issue with cancer is genetic.

As the field of molecular biology matured during the twentieth century it became clear that our physiology was driven by proteins which catalyze chemical reactions in our bodies.

And then came the seminal discovery of the structure of DNA by the collaborative effort of American James Watson and Englishman Francis Crick. The sequences of nucleic acids preserved in the elegant double helix structure of DNA coded for the sequence of amino acids used to synthesize the myriad of proteins needed to not only keep a cell alive and functioning but to properly replicate our genetic code during cell division. Unchecked cell division, the hallmark of cancer, must be connected to our DNA in someway.

Watson and Crick published their discovery in Nature in 1953 and were awarded the Nobel Prize nine years later.

Christofferson’s account of the blossoming field of molecular biology in the twentieth century reminded me of my preparation for medical school thirty two years ago. Unlike most of my classmates in medical school, I was only exposed to this subject after an undergraduate education and a career in engineering. I was captivated.

Chemical reactions, the essence of life, are catalyzed by proteins, massive molecules that exert their effect due to their three dimensional configuration. At this level structure defines function. The designs for all of these proteins are encoded in our DNA which also exists as supermassive molecules called chromosomes, each comprised of some 3 billion atoms delicately arranged in a double helix configuration whose structure allows for portions to be exposed when necessary and protected when not. We understood how our DNA gets transcribed into messenger RNA and how the ribosomes in our cells’ cytoplasm take this RNA and create a chain of amino acids by “interpreting” the sequence of nucleic acids three at a time.

Our cells were the most elegant machines I had ever learned about, combining programming codes, organic chemistry, molecular topology, chemical reaction energetics and feedback loops to keep themselves functioning through a most interesting relationship between amino and nucleic acids.

Having spent a half dozen years writing hundreds of thousands of lines of code prior to ever cracking a cell biology textbook, I knew full well that when a system goes awry you can always trace it to a few lines of code which expresses itself in a way that was unanticipated at the time. If I were to go searching for a cause of cancer, I too would have started with our DNA, the code of life.

With this paradigm in mind it seemed that a breakthrough in cancer treatment was inevitable when in 2003 the Human Genome Project declared that our species’ genetic code had been mapped. This thirteen year effort, reported Christofferson, cost the American taxpayer $3 billion, “the cost of a couple of cafe lattés per capita”. With this monumental accomplishment also came the advent of cheaper and more efficient sequencing technology. At the time of the book’s publishing in 2017 the price of sequencing an individual’s entire genome was $5000. Today, the cost is less than $1000.

Writes Christofferson:

“In the winter of 2005, the highly anticipated announcement came. The NIH held a press conference in Washington D.C. announcing the launch of ‘a comprehensive effort to accelerate our understanding of the molecular basis of cancer through the application of genome analysis technologies, especially large-scale genomic sequencing.’ The grand governmental project was called the The Cancer Genome Atlas. The acronym, TCGA, also cleverly stands for the base pairs of the genetic code.”

TCGA was a consortium of groups some publicly and others privately funded. Bert Voglestein ran a lab at Johns Hopkins University in parallel with the NIH effort. Vogelstein was the most highly cited scientist in 2003 because of his success in identifying mutations of the P53 gene, the most commonly mutated gene in all cancers. P53, is a tumor suppressing gene like RB1, whose existence was deduced by Knudson in 1971 (See Part I). Mutations of P53 appear in 50% of all cancers including Lung, Ovarian, Breast, Colorectal, Head&Neck, Esophageal and others.

With the human genome mapped out, advanced sequencing technology and ample funding in hand, Voglestein was expected to make many more oncogenic discoveries. He never did. Not only were no new oncogenes not found, no specific patterns of previously identified oncogenes were determined to be definitively associated with a type of cancer. Voglestein began with breast, colon and then pancreatic, and the results were the same. In other words, different people with the same kind of cancer had mutations in different oncogenes. This is called intertumoral heterogeneity.

While this doesn’t prove that SMT (Somatic Mutation Theory) is incorrect, it is a clue that there could be more to the picture. If the same kind of cancer could be associated with different patterns of oncogenic expression it leads to the possibility that the mutated genes were not the cause of the cancer at all.

If that weren’t enough, later technology, deep-sequencing, led to another unexpected finding. Deep-sequencing allows researchers to map different cells of the same tumor. This time cancer researchers were surprised to find that different patterns of mutated genes existed within the same tumor. Intratumoral heterogeneity. This is even more suggestive that these cancers weren’t caused by gene mutations but that the mutations resulted from another reason, perhaps a yet to be identified true cause of the cancer.

A Competing Theory: Warburg Effect

Three decades before Watson and Crick were awarded the Nobel prize for their discoveries around the structure of DNA, Otto Warburg, PhD, had won his own for explaining how cells use oxygen to create usable energy for life. Part of his discovery included the identification of a key enzyme involved in this reaction called cytochrome oxidase.

Some of the foundational work which led to his discovery involved his observation of rapidly dividing cells of a sea urchin embryo after fertilization decades earlier. He proved that cell division must require substantial energy by confirming through meticulous measurements, that their oxygen consumption substantially increased.

As Virchow established much earlier, rapid cell division is the definitive characteristic of cancer too. Using the delicate instrumentation which he independently developed to measure gas exchange, he discovered that unlike healthy rapidly dividing sea urchin cells, cancer cells, which were also explosively dividing, were generating lactic acid, the byproduct of a much less efficient pathway called fermentation, an ancient mechanism available to some cells in our body when oxygen isn’t present in sufficient quantity.

Writes Christofferson:

“Years later, Warburg made another critical observation that hinted at why cancer cells were fermenting in the first place. He showed that when normal, healthy cells were deprived of oxygen for brief periods of time (hours), they turned cancerous. No other carcinogens, viruses or radiation were needed, just a lack of oxygen. This led him to conclude that cancer must be caused by injury to the cell’s ability to respire. He contended that once damaged by lack of oxygen, the cell’s respiratory machinery (later found to be mitochondria) became permanently broken and could not be rescued by returning the cells to an oxygen-rich environment. He reasoned that cancer must be caused by a permanent alteration to the respiratory machinery of the cell. It was a simple and elegant hypothesis. Warburg would contend until his death that this was the prime cause of cancer.”

Cancer cells have a rapacious demand for glucose due to their increased need for energy combined with their inability to generate it efficiently. The Warburg effect is in fact the basis for why PET (Positron Emission Tomography) scans are used to identify potentially cancerous lesions in a patient’s body.

Something had gone awry with cancer cells. They had to partially rely on fermentation even though oxygen was readily available. Cancer was not made up of “superhuman” cells which refused to die, they were partially damaged and potentially rendering them susceptible to a means of eradication involving energy synthesis.

What might such means of eradication look like?

3-BromoPyruvate

One answer begins back at Johns Hopkins University. A decade before Bert Voglestein began his study of the oncogene p53, Pete Pederson was a post-doc working for Albert Lehninger, the researcher who discovered mitochondria, the organelles responsible for cellular respiration. Pederson made some important discoveries including these:

The most rapidly growing tumors had the least number of mitochondria and were producing the most amount of lactic acid, the byproduct of fermentation.

The mitochondria in cancer cells were overproducing an isoform of an enzyme called hexokinase II which primed glucose for the first step in a biochemical pathway called glycolysis. Unlike normal hexokinase which will slow its activity in the presence of excess glucose, hexokinase II won’t stop “shoving glucose down the fermentation pathway”.

Then, in 1991, Pederson took on another post-doc researcher, Young Hee Ko. Ko attacked the problem from the back end. Lactic Acid, the byproduct of fermentation is toxic to the cell and must be eliminated. This is done through molecules called Monocarboxylate Transporters (MCTs). Ko knew that MCTs would be upregulated in cancer cells and discovered that a readily available and simple molecule called 3-Bromopyruvate (3BP) can enter the cell through MCTs and inhibit the function of hexokinase II. At the same time lactic acid must compete with 3BP to leave the cell. 3BP is a double whammy to cancer cells.

The story of Pederson, Ko and their decades-long collaboration is both inspiring and frustrating.

Ko was skeptical that such a simple and cheap molecule could even work in vitro. By Christofferson’s account, her results were stunning in head to head comparisons with “chemotherapeutic heavy hitters” like carboplatin, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, 5-fluorouracil, methotrexate and paclitaxil. Moreover the molecule vastly outperformed all these other agents in every cancer type she examined.

Despite her shimmering results, she still had to urge Pederson to let her try the molecule on animal models. It didn’t seem possible that there would be a simple solution to such an intractable disease. Nevertheless, it worked swimmingly well. The tiny, cheap molecule was ready to be trialed in human beings, and that’s when a strange series of funding setbacks hit Pederson and Ko.

Ko was eventually responsible for spearheading one of the only experiments of 3BP on a human being. The patient was a Dutch adolescent named Yvar Verhoeven who was dying from Hepatocellular Carcinoma, liver cancer. They young man had fist-sized tumors which took over 95% of his liver. The family had exhausted all treatment possibilities and his father reached out to Ko for help.

After many struggles to find a physician and institution that was willing to administer it, the potential drug was finally deployed while young Yvar was on his death bed. The boy tolerated several treatments and began to feel better, reporting an appetite for the first time in months.

And then his neurologic status declined. It was soon discovered that his ammonia levels were high, a sign of tumor lysis syndrome. His body was being flooded with the remnants of tumor cells that were dying off rapidly. 3BP was working, too well. He recovered, the dose was adjusted and another medicine to mitigate the rise in ammonia was added.

The tumors which had taken over most of his liver were eliminated. On his way to make a stunning recovery that shocked his family and physicians, he traveled to the United States to celebrate his 18th birthday with Ko’s team and speak to the first year medical students at Johns Hopkins about his experience with the new miracle cure. He contracted a respiratory infection on his journey home. Unable to tolerate the antibiotics he needed to treat a pneumonia, Yvar died, but not from cancer.

Conclusion

The evidence for a metabolic theory of cancer is substantial:

Warburg’s early experiments proved that there is a derangement in the ability cancerous cells have to create energy.

This abnormality is the basis for one of the most widely used means of detecting cancer, the PET scan.

There is a direct relationship between the aggressiveness of a tumor and the amount of lactic acid its cells were producing.

The problem was traced to the over expression of an isoform of the enzyme, hexokinase and interference with this isoform, hexokinase II, leads to significant tumor death as 3BP has shown in vitro and in vivo.

Warburg demonstrated that this metabolic problem could be induced in healthy cells which are damaged by a period of hypoxia—no carcinogens are necessary.

Taken together it explains why hybrid cells with cancerous cytoplasm remain cancerous while hybrid cells with a cancerous nucleus remain healthy.

While this in no way disproves that some cancers are indeed genetic in etiology it raises serious questions:

Why does the National Cancer Institute continue to aver that cancer is a genetic disease given inter and intratumor heterogeneity?

Why have crude cancer mortality rates barely budged despite the staggering expense of oncologic drugs?

Why has the mapping of our genome not led to the identification of more oncogenes?

Despite the long history of the evidence for cancer as a metabolic disease why are there only a handful of Phase I clinical trials of drugs that exploit this pathway today?

I asked my oncology buddies about the metabolic theory of cancer. Said one,

“I’m not familiar with the theory at all. I’m guessing that oncologists are not aware of it.”

Another had more to say:

“Maybe Warburg was onto something for certain cancers. Disorders of the Krebs cycle, the metabolome is an area of current research even if perhaps not at the front of the room. There are so many dedicated scientists looking at all sorts of stuff, sadly now losing their funding!

Patients do bring in text books regarding the Warburg theory from time to time and use ivermectin, ketone diets and all sorts of things which apparently have some basis in this theory. I just had a patient with metastatic colon cancer follow this plan and his tumors grew and spread and he recently died, certainly didn’t work for him. He was a bright guy who read vociferously on this subject and very much believed it. I think it is more complex in most cases.”

Given that one oncologist was unfamiliar with the theory and the other seemed to know about it from his patients, it would seem that the metabolic theory is not considered seriously by the orthodoxy.

Finally, it is worthwhile to highlight some insights the author shares at the end of the book.

Cancerous cells are generally regarded as the result of genetic mutations that have endowed them with superhuman tenacity. They replicate unchecked, avoiding our immune system which serves to identify threats throughout the body. They grow into tumors that crowd their way into tight spaces, causing pain or obstructing the flow of life. Worse yet, they can seed areas far from their origin. They spread like cancer.

Writes Christofferson:

“Cancer is perceived as a predictable manifestation of a universe that tends toward chaos—one that favors disorder over order. It is seen as accidental. Although the origin of cancer may be the result of chaos, the disease itself is anything but. It takes a remarkable amount of coordination to do what cancer does, to go through the elaborate functionality of the cell flawlessly and repeatedly. To transition to energy creation by fermentation means that the cell must drastically alter its enzymatic profile in an orderly manner. To direct the growth of new vessels to feed the growing mass takes an exquisite series of operations. Cancer is a disease of order, and every step of the way, it is directed and coordinated from somewhere.”

While the establishment largely focuses on our DNA, the competing school of thought believes the problem lies in a cell’s metabolism, either primarily or secondarily. In the passage above the author offers us another contrast between the two groups. When cancer is seen as primarily a metabolic problem, malignant cells aren’t the tenacious survivors which refuse to succumb to the harshest poisons, they are regarded as defective and vulnerable to interventions that target their weakness: their inability to nourish themselves efficiently.

Christofferson notes that this contrast bubbles up into the attitude of researchers who pursue the metabolic theory. They are enthusiastic, they believe they are on the verge of something big. Cancer cells are seen as damaged, clinging to life by an ancient thread of metabolism leaving them susceptible to stressors that healthy cells can shrug off, lending credence to other modalities like hyperbaric oxygen therapy which creates oxygen free radicals that have been shown to selectively damage cancerous cells. Simple interventions like ketogenic diets and fasting have also shown promising results, once again supporting the metabolic theory.

Given the fact that targeting the metabolic pathway can be done relatively cheaply and with less toxicity to healthy cells, is there a good reason why we aren’t exploring this strategy more?

Please leave your comments.

There is a reason of course for the lack of exploration in regard to this possibility and it is not a good one. Cancer treatments are the big money spinners for the Pharma industry and perhaps unconsciously, there is more money in selling a dream and a few more months or years of life, than there would be in a cure.

The power of the Pharma industry with its tentacles completely embracing Allopathic medicine where it dictates how doctors are trained and in what they are trained, and extending into the political sphere where money always talks loudest. is why drug, knife and techo toy medicine is the only modality allowed.

All diseases manifest differently in different people which says, since no generic humans exist, there must be a variety of factors at work beyond the material and mechanical and they would include emotional, psychological, spiritual, environmental, circumstantial and more. There is little to no money in the last five possible factors but an absolute fortune to be made in the first two. That is the problem and that will remain the problem as long as conventional medicine is a profit and power driven industry instead of a healing modality.

As someone recently diagnosed with and currently undergoing treatment for lymphoma, and as someone understanding at most half of what you write about here, I give you my 5 cents: First, I am missing the 'the bad cells refuse to die'/apoptosis angle that seems to be the problem in my case, maybe you can explain where that fits in here.

Then, I noticed that my doctors and pharmacists (Top 10 cancer hospital World) have very little knowledge about, nor interest in discussing, anything outside of the box, whether that's the cause of it, or supplements/diet (often even contradictory advise given) or trials that they don't participate in directly.

They fully trust in and focus upon their established diagnostic and treatment approach and their available tools only (even recommending masks, flu and Covid shots....) and I really have no choice but to do so too, and in this case also strongly do (bar the mask&'vaccine' etc. quackery, of course) in light of the good hands I seem to be in there and the apparent progress made in that particular area traditionally over the last decade.

But in light of the relatively long time between initial diagnosis and treatment start, I really also would have liked to- and wonder why I haven't even been legally able to here- at least give the Tippin protocol or something like that (cheap, no side effects) a try as well, or why no trial has been set up for that yet?

It really reminds me very much of Covid, where any such deviation from the pre-chosen gene therapy path was actively and brutally sabotaged, instead of being pursued in order to improve outcomes and maybe even make a breakthrough discovery along the way.

I also stumbled across the Burzyinski stuff by chance and again, I have no idea whether that's a scam, magic or something in between, but why the default ignorance and vilification by the pharma&=media establishment for decades, instead of just a serious effort by them to research into this properly? If it was available and less expensive, I certainly would have liked to be at least given a chance to give it a try, before starting with the traditional treatment, if that was then still needed.

So, I am grateful for the progress made in traditional oncology and that I haven't been diagnosed with cancer two decades earlier, but I am also cognizant now and disappointed that, again (Covid, HIV, 9/11, man-made climate change etc.), not everything is really being tried and pursued with an open outcome mind, aka scientifically, in this area.

I think the drivers and reasons for all that are sadly very obvious and pretty much equal to the Covid response ones on financial and human psychology levels, bar the outright malice of many if not most actors in Covid's case.