It's Tax season! Yippee!

A glimpse at the most diabolical and insidious efforts to erode our prosperity

While walking our dog this morning I was considering writing about something of which I have only a journeyman’s understanding. The subject is economics and monetary policy. Yes. I sense that you are at the edge of your seat in anticipation of what is to follow.

Satya was the smallest of the litter born to a rescue dog from Tennessee. She’s almost four now. As is customary in Indian tradition, we name our children after things that we wish or aspire for. It is thought that when we call their name we are simultaneously requesting the Universe to bring what we vocalize into our lives. Satya means “truth” in Sanskrit, something that we believed we needed the most in September, 2020 when we adopted her.

We live in a town that has no leash law. Satya has adapted to the freedom very well. She is very friendly with dogs and people of all sizes and ages. She always comes when we whistle for her. She is also fond of playing fetch.

This morning, she sensed our walk was coming to an end so she darted off to find a stick of her liking to extend our time outdoors together. A couple approached me as I was heaving the stick for the umpteenth time.

“If only we could be so happy chasing a stick over and over again!”, the woman commented.

I looked at her and paused.

“We are”, I replied, “we just happen to choose different kinds of sticks”.

I interpreted her observation as a sign that I should put pen to paper.

We all have different sticks that we chase. Most are temporary surrogates for what we really desire. However in our pursuit of material wealth, health, time, fame, love, etc. we learn a great deal about ourselves, each other and the world around us. Thus, there is some real utility in perfecting how we “fetch”. But are we working harder than we need to? Is someone else benefiting from our effort and labor?

Yes, there is. In this article I intend to unpack how and why we have been duped by a system that is rigged against us.

Economics 101

I am not an expert in economics. In my limited research into the topic I can only say that the deeper I look into economic theories and models the more uncertainty enters the picture. I will stick to the basics, the stuff that cannot be contested. For those readers who are well-versed in monetary theory what follows here will be just a graze for you, and I welcome your critique, comments and suggestions.

I took some classes in economics in college. I had the good fortune of hearing Robert Solow lecture twice a week. Attendance was always very high, and there was always a buzz in the lecture hall. We undergrads were lucky indeed. Just a few months before Solow was assigned to teach our class he won the Nobel prize for his contributions on the theory of economic growth.

Of course we didn’t learn anything groundbreaking from him. He was tasked with teaching us intermediate macroeconomic theory after all. Nearly 40 years later, I recall very little of the specifics he tried to impart to us. However I do remember very well that he had a lovely way of explaining things, making a rather dry subject fascinating.

I left with the impression that we had only skimmed the surface of very complicated theories. Solow alluded to the fact that economists’ models require the most computational power than models in any other subject of study. There are an endless number of variables with differing weights and interrelationships. It’s like trying to predict the weather— or what the climate will be in a few decades…

Tax day this year is April 15, the day by which you must tell the IRS how much you owe them or request an extension to do so. But “Tax Day” is a relatively recent thing. Prior to 1913, there were no taxes levied upon income. The sixteenth amendment was passed by Congress in 1908 and ratified in 1913.

But why did we need to tax income for the first time then? There were no major calamities requiring massive public expenditures. We weren't fighting any prolonged conflicts. The Revenue Act of 1913 was supposedly passed by Congress in order to offset the desire to reduce tariffs, the main form of government revenue at the time.

The Democratic Party argued that high tariffs constituted an unfair burden on poorer people because it drove prices up. In exchange for reducing average tariff rates from 40 to 26%, we the people would have to pay a 1% tax on income over $3000 per year. Reduced tariffs would decrease prices for everyone. Only 3% of the population, the highest earners, would be burdened by the new form of taxation. That seems reasonable. What could go wrong?

Fast forward 111 years, 60% of Americans now pay income taxes. The highest earners pay a 37% tax on their income. And as is well known, the ultra-rich manage to maneuver and hide most of their earnings through loopholes and shelters that have become part of a tax code that is clearly spelled out in just under 75,000 pages.

Today, one out of every $2 of governmental revenue is in the form of taxes on our income, a source that didn’t exist prior to 1913. What happened? What is the government buying now that they didn’t back then?

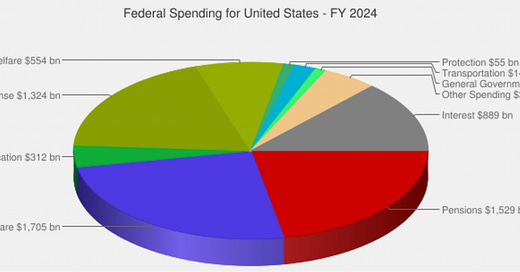

We now have Medicare, Medicaid, Social Security and Welfare. These are the “Entitlement” Programs that are the safety net for the elderly and financially insecure. We also have two other massive annual expenditures:

In 2024, over 1.3 trillion (that’s 1,300,000,000,000) dollars are allocated to keep us and our allies safe from people who are jealous of our freedoms, or, in my opinion, countries who are enraged at our decades-long history of picking fights and subjugating populations to our particular interpretation of how things ought to be. Here’s a quick animation that depicts the military budget as a portion of US Discretionary spending.

Discretionary spending excludes funding for entitlements. The dollars are inflation adjusted. There are two points that become clear.

It doesn’t matter which party is in power. Our government does the same thing with the money we have earned from our hard work. The two party system is an illusion, practically speaking.

More than half of what is left after paying for entitlements goes to the military.

Of course many would argue that this is necessary. We have since fought two World Wars, a war in Korea and a prolonged conflict in Vietnam. We also had to oust Saddam from Kuwait and then destroy Iraq in search of non-existent weapons of mass destruction, ransack Afghanistan over two decades in search of Osama bin Laden. We were told that the purported mastermind of the 9/11 attacks was eventually found living in Pakistan and immediately killed by Navy Seals before he could be questioned publicly or behind closed doors.

If you have any doubts about the identity of the person killed in this courageous operation upon his modest residence, be assured that his identity was confirmed by a handful of people who then dumped his body into the ocean some hours later. We were finally able to sleep soundly again knowing that although the challenges we face can sometimes be very expensive, America and freedom will always prevail. However, just to be sure, it’s safer for everyone if you remove your shoes while going through TSA security at the airport.

Putting aside the justification for these conflicts and the resultant need for our national security, how do we pay for all of this? The answer is most of the time we can’t. There are only a few years in the last few decades where our government collected more than it paid out. All the rest have been deficit years:

This is why we now have another big expense: interest on the debt our government has accrued over the years. In 2024, the interest on the approximately 30 trillion dollars we have borrowed will be almost 900 billion dollars.

During the years in red we borrow the dough from the people and countries who loan us the funds through their purchase of Treasury Bonds, Bills and Notes. That’s awfully kind of them (of course we pay them interest on the bonds and notes). But the demand for these securities do not always match our needs. Thankfully we have something called the Federal Reserve, our nation’s central bank, which can step in to save us. Over the years the Fed has been shouldering more and more of our nation’s debt:

Thank you Federal Reserve!!

But where does the Fed get trillions of dollars to loan us in order that we can fight the good fight abroad or, as in the last three years, pay for miraculous vaccines, aid the businesses that were forced to shut down, pay unemployment checks, etc. etc.?

I will dispense with the cheeky tone and get to the point. The Fed doesn’t have it. They conjure it up with a few strokes on a computer once they get the go ahead from the government. The money doesn’t exist until the government needs it. It’s a very convenient arrangement that was made possible by the Federal Reserve Act which was signed into law by President Wilson on December 23, 1913.

Hopefully that year should ring a bell. Wilson also signed the The Revenue Act of 1913 two months earlier in October of that same year. How interesting.

The Federal Reserve Act was sold to Congress and the people as a way to create a safety net for banks that in the past lent money too aggressively and found themselves insolvent, destroying the lives of the people whose money they held.

The circumstances behind the passage of the Federal Reserve Act are fascinating and disquieting. I highly recommend reading The Creature From Jekyll Island by G. Edward Griffin for an excellent examination of this subject.

Banks had been able to take short term loans from other banks when withdrawals exceeded their reserves on hand. However if and when widespread panic occurred the outcome would be devastating for many. Now, banks that follow the Fed’s rules for lending would have access to funds that only the Fed could provide.

As an aside, the rules on lending are quite lenient. A lending institution needs to have only about 10% of the amount they lend in reserves. This is called “fractional reserve lending”. Perhaps the most twisted aspect of these “restraints” is that this system regards loans as income streams, or assets of the bank too. This classification means that when a bank obtains a signed promissory note for a million dollar loan, that million dollars is considered an asset of the bank which can be used as the basis of lending another $900,000 to someone else.

But the Federal Reserve is more than just a bank’s bank. As alluded to above, the Fed is endowed with the unique power to adjust the supply of money in our economy by indirectly setting interest rates. Dropping the interest rate, the cost of debt, encourages borrowing and the creation of dollars. Raising it encourages debt repayment and money disappears from the economy.

When the amount of money in circulation increases it will have at least one eventuality: inflation. Though the public generally believes that wide spread inflation arises of its own, it is in most cases the direct result of the Fed’s monetary policy. Inflation is better thought of as currency devaluation.

If more money is placed in circulation, prices will eventually rise. Rising prices motivates people to buy now rather than later. This in turn increases the demand for loans and just like with public deficit spending, the more loans we take, the more the monetary supply expands, stimulating growth while further fueling inflation.

The Federal Reserve also has the unique ability to interrupt this positive feedback loop by raising the cost of borrowing and encouraging repayment of debt. Such contraction cycles are necessary to thwart the devaluation of our currency and are associated with falling investments, job losses, business insolvency and hence the unpopularity of whatever administration is in power.

Thus, the Fed controls the the throttle and the breaks of our economy.

With the passage of the Federal Reserve Act, the Fed was given the power to control our country’s monetary supply, and in granting this institution that power, the government was given the power to control its peoples’ productivity and activity.

For example, there are obviously those amongst us that supported the war in Afghanistan which spanned nearly two decades and cost us over six trillion dollars. How much of the public would have supported this war if everyone had to write a $100 check every month for the 20 years our troops were in Afghanistan (I am estimating that the six trillion dollars would be shouldered by 200 million taxpayers)?

Deficit spending made possible by the Federal Reserve allows the population to defer expenses for years or even generations. Prolonged military conflict, an extremely expensive undertaking, is only feasible if there is a central bank in play.

The Takeaway

Nobody likes inflation. As mentioned above, inflation is better thought of as currency devaluation. The more inflation is up, the less the money in your bank account is worth. Governments don’t like it either. Administrations lose popularity when prices are high. “It’s the economy, stupid.”

Central bankers also don’t like too much inflation. Their power comes from their authority to manipulate the amount of money in circulation. The effect of their interventions are directly related to the value of the money supply they indirectly control.

This brings us back to the point in our nation’s history when both the Federal Reserve and income taxes were brought into existence. Recall that the 16th amendment was passed by Congress in 1908, but didn’t get ratified until two months before the Federal Reserve Act.

Was it just a coincidence that these two transformative laws that handed over incredible power to a new, independent entity that ostensibly acts in the public’s interest and opened the door for our government to tax our earnings were passed within months of each other? Or was an income tax planned and then simultaneously introduced to prevent runaway inflation from unabated governmental spending that was envisioned by those who were really running this country?

But central banks are also concerned with inflation rates that are too low. Central banks around the world are very transparent about their inflation target. 2%. That’s their goal. A 2% inflation rate is considered to be present in a “productive” economy. Why?

Some inflation, we are told, is necessary for productivity. If prices were not gradually increasing, there would be less incentive to buy or invest now, and hence, “productivity” would suffer. It is also true that demand for loans (i.e. income streams for banks) would diminish.

Though many feel validated when a lender approves them for a car or home loan, banks want to loan as much money as possible. They make their revenue through the interest they charge their debtors. In fact, banks operating under the Federal Reserve umbrella must abide by their limits on how much they can lend to people like me and you. With access to the Fed’s power to conjure money out of thin air to save them from a run on their reserves, they have little incentive to be overly prudent.

So what do they mean by “productive”? Most economists agree that without some degree of inflation economies would contract and people would lose their jobs. This is sensical, but how much would economies contract? In the end, people still need clothes, food, shelter, fuel, phones, computers, cars, vacations, etc. They will always be willing to work and/or invest to pay for these necessities and luxuries.

These are the sticks that we chase. To me, it seems highly questionable that anyone would need to goad the people of this world into buying now by orchestrating the devaluation of their wealth every year. This magical 2% goal isn’t what we think it is. It isn’t representative of any growth in our prosperity. It is better thought of as the slope of a hill we collectively must climb to get to the sticks we want. The extra labor required to climb that hill flows into lending institutions, the beneficiary of the interest we pay them on money which they bring into existence the moment we promise to pay them back.

Although it is sold as a balance between economic growth and hyperinflation, it’s not so difficult to see that a 2% inflation rate is enough to drive enough money into the hands of our lending institutions to satiate their greed while keeping us blind to the reality that our prosperity is being eroded at a rate that isn’t so easy to apprehend in the short run.

How would we know this is happening? It should be obvious. Fifty years ago a young family of four could own a home and a car and take annual vacations on a single, non-professional salary. Now it isn’t uncommon that professionals are living in their parents’ homes into their thirties, saving for a down payment on a house and waiting for the time they can afford to have children of their own. Why is everything so much more expensive?

The other disquieting reality of our plight is that central banks can fund any level of governmental expenditure with fiat currency. A tremendous amount of money flows into commercial banks on the back end of deficit spending in the form of interest payments. How do banks view wars, pandemics and other disasters, events that require immense governmental spending?

Are the endless wars and repeated disasters happening of their own? Or are they being engineered by those who make vast sums on interest on the debt required to pay for them?

What is your intuition telling you? Please leave your comments.

For someone who describes himself as having only a "journeyman's understanding" this article certainly helped to clarify my own understanding, so thank you.

Thanks for this article. To elaborate a few things:

You don't need a Federal Reserve to fund big deficits. Lincoln paid for his war by issuing greenbacks, which were simply bills printed by the Federal Gov't.

While inflation causes problems, deflation can be even worse because debtors, many of whom are poor, get extra-screwed.

An alternative to the tax on incomes, favored by many in Congress (and Pres. Taft) at the time, was a tax on inheritances. But the income tax was supported by the single-taxers, because it could have been configured to collect land rent.

Unique among Constitutional Amendments, the 16th (income tax) was ratified under a special rule, providing that once a state had ratified, it could not withdraw the ratification, but a state that had voted against the amendment could reconsider and ratify it.

Really good (and well-documented) videos on the Federal Reserve and World War I (as well as many other topics) have been done by James Corbett at corbettreport.com