Coming To

What does our ongoing search for the mechanism of inhaled anesthetics tell us about our consciousness and our world?

There’s an aphorism in anesthesiology that is often offered to young residents early in their training:

“It takes an internist three days to kill a patient. It takes a surgeon three hours. It only takes an anesthesiologist three minutes…”

Although it may sound like a morbid indictment of physicians’ intentions, it is actually meant as a reminder to the trainee of how easily irreparable harm can ensue if a doctor isn’t paying attention to their own biases in their assessment of a patient’s condition.

How soon will a doctor realize that their choice of therapy is actually doing more harm than good? It depends on the kind of medicine that is being practiced. It can take a few days for a patient’s deteriorating condition to be attributed to poor medical therapy. A patient in a surgeon’s care may bleed to death if the surgeon chooses to delay an operation or cannot find the “bleeder” in the operating room.

Anesthesiologists, on the other hand, are trained to restore oxygenation to the brain and body in times where a person’s airway is compromised or when they are rendered incapable of independent respiration through anesthetics themselves. Three minutes. That’s how long the delicate neurons in our brains can survive without oxygen.

I remember being asked by my mentors to hold my breath until I successfully placed a breathing tube through the larynx of an unconscious patient who was unable to breathe for themselves. This kind of exercise was meant to remind me of how quickly sixty seconds go by when performing a delicate maneuver with full attention. How long was I willing to struggle before looking for other options or making adjustments? The answer becomes quite clear in about a minute or so.

I have often wondered if this kind of training has made me more facile in adapting to circumstances that are rapidly changing or whether it has caused me to second guess myself more often than is necessary.

We have other aphorisms too. Sometimes patients ask us what we charge for “putting them to sleep”. You can bet that most of us will respond the same way: “No charge! We only bill you for the waking up part…”

This isn't our way of casually deflecting a reasonable question. It is meant to serve as a gentle reminder to both parties regarding the importance of “coming to.” If we couldn't regain consciousness what would be the point in having the surgery in the first place? Nobody wants to experience pain and fear if it can be avoided. If the only way to avoid the pain of an operation is to temporarily be rendered unconscious, most people will readily and willingly consent to that, as long as we can return to our natural state of being alert and interactive with the world around us. We are awake and aware and that--rather than any particular conception of health--is our most precious gift.

From my point of view, we really shouldn’t charge for “putting someone to sleep”. It’s too easy. With today’s medications, putting someone to sleep, or in more correct terms, inducing general anesthesia, is straightforward. Two hundred milligrams of this and fifty milligrams of that and viola : you have rendered a person completely unconscious and incapable of even breathing independently.

Some of the medications we administer at induction are similar to the lethal injections executioners use. Unlike executioners, we then intervene to reestablish their breathing and compensate for any large changes in blood pressure, and the patient thereby survives until consciousness miraculously returns sometime later.

The Mystery and History of Anesthesia

In addition, those in my field have to contend with the actuality that we really don’t know what we are doing. More precisely, we have very little, if any, understanding of how anesthetic gasses render a person unconscious. After 20 years of practicing anesthesiology I still find the whole process nothing short of pure magic. You see, the exact mechanism of how these agents work is, at present, unknown. Once you understand how a trick works, the magic disappears. With regard to inhaled anesthetic agents, magic abounds.

In 1846 a dentist named William T.G. Morton used ether to allow Dr. Henry J. Bigelow to partially remove a tumor from the neck of a 24 year old patient safely with no outward signs of pain. The surgery took place at Massachusetts General Hospital in front of dozens of physicians. When the patient regained consciousness with no recollection of the event it is said that many of the surgeons in attendance, their careers spent hardening themselves to the agonizing screams of their patients while operating without modern anesthesia, wept openly after witnessing this feat.

At the time no one knew how ether worked. We still don’t. Over the last 174 years, dozens of different anesthetic gasses have been developed, and they all have three basic things in common: they are inhaled, they are all very, very tiny molecules by biological standards and… we don’t know how any of them work.

If you closely consider how our bodies do what they do (move, breathe, grow, pee, reproduce, etc.) the answers may be astounding. It is obvious that the energy required to power biological systems comes from food and air. But how do they use them to do everything? How does it all get coordinated?

These are the fundamental questions that have been asked for millennia, by ancient medicine men to modern pharmaceutical companies. It turns out that the answers are different depending on what sort of perspective and tools we begin with.

In the West, our predecessors in medicine were anatomists. Armed with scalpels, the human form was first subdivided into organ systems. Our knives and eyes improved with the development of microtomes and microscopes giving rise to the field of Histology (the study of tissue). Our path of relentless deconstruction eventually gave rise to Molecular Biology and Biochemistry.

This is where Western medicine stands today. We define “understanding” as a complete description of how the very molecules that comprise our bodies interact with one another. This method and model has served us well. We have designed powerful antibiotics, identified neurotransmitters and mapped our own genome. Why then have we not been able to figure out how a gas like ether works? The answer is two-fold.

First, although we have been able to demonstrate some of the biological processes and structures that are altered by an inhaled anesthetic gas, we cannot pinpoint which ones are responsible for altering levels of awareness because inhaled anesthetic agents affect so many seemingly unrelated things at the same time. It is impossible to identify which are directly related to the “awake” state. It is also entirely possible that all of them are, and if that were the case consciousness would be the single most complex function attributed to a living organism by a very large margin.

The second difficulty we have is even more unwieldy and requires some contemplation. As explained above, western medicine has not been able to isolate which molecular interaction is responsible for a gas like ether’s’ effect on our awareness. It’s reasonable to approach the puzzle from the opposite end and ask instead, “Where is the source of our awareness in our bodies?” and go from there.

It turns out that the answer to this question is still far from resolved. Several structures in the prefrontal and posterior cortex as well as the brainstem have been proposed as the source of awareness. It could be some them. It might be all of them. However, if we attribute consciousness to those specific structures, then we are necessarily identifying them as what are awake. To find the mechanism of their “awakeness” we must then look closer at them. With the tools we have and the paradigm we have chosen we will inevitably find more molecules interacting with other molecules. When you go looking for molecules that is all you will find.

Our paradigm has dictated what the nature of the answer would be if we ever found one. Does it seem plausible to think we will find an “awareness molecule” and attribute our vivid, multisensorial experience to the presence of it? If such a molecule existed how would our deconstructive approach ever explain why that molecule was the source of our awareness? Can consciousness ever be represented materially?

I don’t think it can. This is why I believe a more sensible approach would be to consider the activity of these structures in the brains of conscious individuals as evidence of consciousness, not the source of it. In my view, our long search for the mechanism of ether and other inhaled agents has brought us to the boundary where the physical world ends and metaphysics begins.

The mechanistic nature of our model is well suited to most biological processes. However with regard to consciousness, the model not only lends little understanding of what is happening, it also gives rise to a paradigm that is widely and tightly held but in actuality cannot be applied to the full breadth of human experience. We commonly believe that a properly functioning physical body is required for us to be aware. Although this may seem initially incontrovertible, upon closer examination it becomes quite clear that this belief is actually an assumption that has massive implications.

To be more precise, how do we know that consciousness does not continue uninterrupted and only animate our physical bodies intermittently rather than the other way around where the body intermittently gives rise to the awake state? At first this hypothesis may seem absurd, irrelevant and unprovable. Putting absurdity and lack of relevance aside, there isn’t any scientific proof that our consciousness terminates with the death of our bodies either.

We are left with two different paradigms, neither which can be proven by the standards we have available. However the paradigm to which we subscribe is far from irrelevant. Let’s now take a closer look at what we can observe when people have a brush with death or actually “die” by our standards. Is nature providing us any hints?

How do we know a patient is “asleep”?

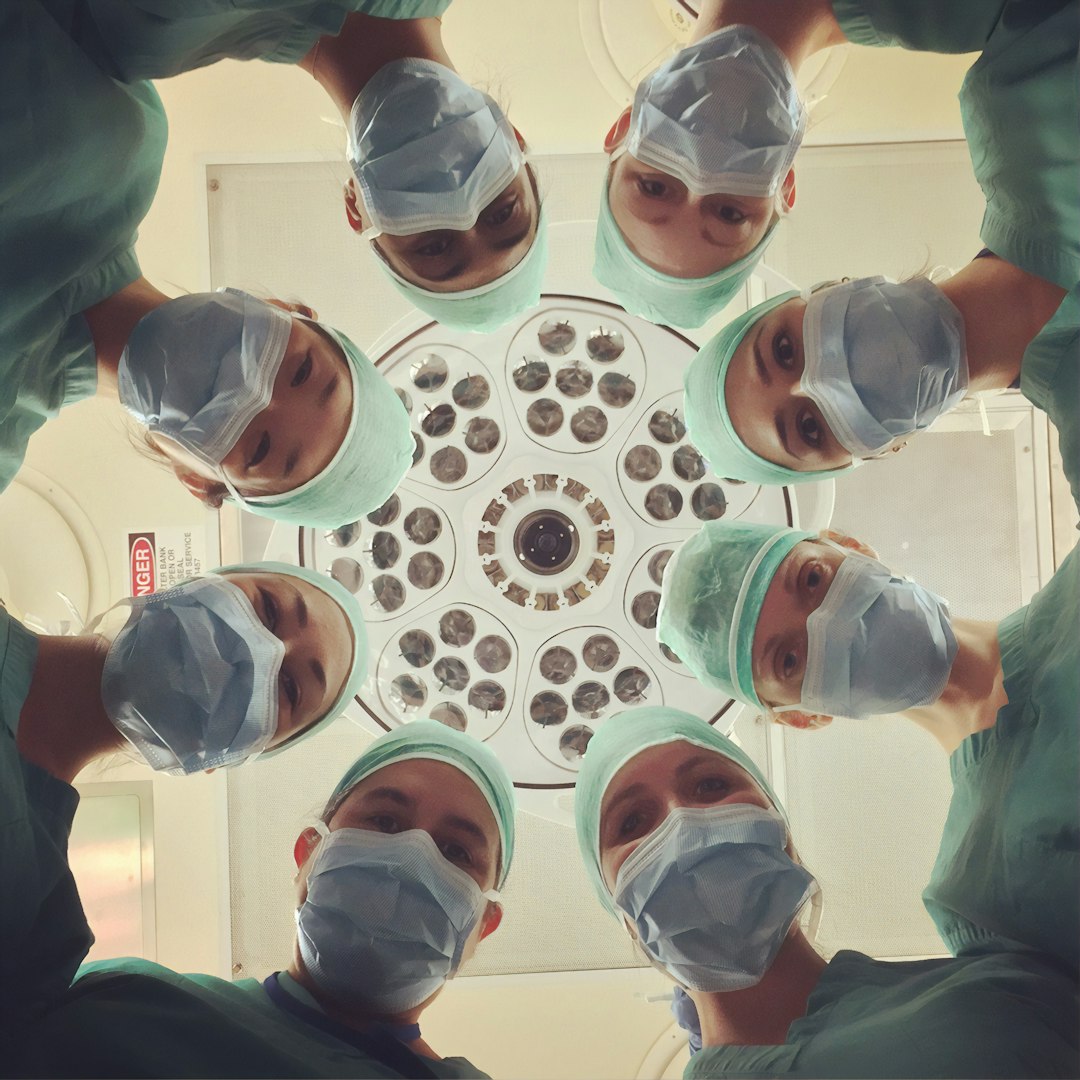

Patients under anesthesia offer a unique look at the question because they are rendered inanimate, unconscious and as close to death as is possible before they are returned to their normal state.

Let us first consider how anesthetists measure anesthetic depth in the operating room. They continually measure the amount of agent that is circulating in a patient’s system, but as described earlier, there is no measurable “conscious” molecule that can be found. They must assess the behavior of their patients to make that determination. Do they reply to verbal commands? Do they require a tap on the shoulder or a painful stimulus to respond? Do they respond verbally or do they merely shudder or fling an arm into the air? Perhaps they do not even move when the very fibers of their body are literally being dissected.

Here’s where things get interesting. There are many situations when a person will interact normally for a period of time while under the influence of a sedative with amnestic properties and then have absolutely no recollection of that period of time. As far as they know, that period of time never existed. Indeed, this reproducible phenomenon requires a relatively small dose of drug in the benzodiazepine class (e.g. Valium or Xanax).

A patient may have no idea that they were lying on an operating room table for 45 minutes talking about their recent vacation while their surgeon performs a minor procedure with local anesthesia on their wrist, for example. Sometime later they find themselves in the recovery room when to their profound disbelief they notice a neatly placed surgical dressing on their hand. More than once a patient in my care asked me to remove the dressing so that they could see the stitches with their own eyes.

How should we characterize their level of consciousness during the operation? By our own standards they were completely awake. However, because they have no memory of being awake during the experience, they would recount the experience more or less the same way a patient who was rendered completely unresponsive would. This phenomenon is common and easily reproducible. Moreover, it invites us to consider the possibility that awareness continually exists without interruption but we are not always able to access our experiences retrospectively. We then commonly but inaccurately describe these events as “losses of consciousness”.

During some procedures when a surgeon is operating very close to the spinal cord anesthetists will infuse a combination of drugs that render the patient unconscious but allow all of the neural pathways between the brain and the body to continue to function normally so that they can be monitored for their integrity. In other words, the physiology required to feel or move remains intact, yet the patient apparently has no experience of any stimuli, surgical or otherwise, during the operation.

How are we to reconcile the fact that we have a patient with a functioning body but has no ability to experience it? It would not be so wrong to say that that which experiences is not part of the physical body. This raises another philosophical question: Who exactly is the patient in this situation?

Near Death Experiences (NDEs)

If we broadened our examination of human experience to consider more extreme situations, another wrinkle appears in the paradigm. Near Death Experiences (NDEs) are all characterized by lucid awareness that remains continuous during a period of time while outside observers assume the person is unconscious or dead. Sometimes patients who have experienced an NDE in the operating room can accurately recount what was said and done by people attending to them during their state of clinical death. They are able to accurately describe the event from an observer’s perspective, often viewing their own body and those around it from above.

Interestingly, people describe their NDEs in a universally positive way. “Survival” was an option that they were free to choose. Death of their body could be clearly seen as a transcending event in their continuing awareness and not as the termination of their existence. Very often the rest of their lives are profoundly transformed by the experience. No longer living with the fear of mortality, life subsequently opens up into a more vibrant and meaningful experience that can be cherished far more deeply than was possible prior to their brush with death. Those who have had an NDE would have no problem adopting the idea that their awareness exists independently of their body, functioning or not. Fear and anxiety would still probably arise in their life from time to time, but it is the rest of us who carry the seemingly inescapable load of a belief system that ties our existence to a body that will perish. How does this belief serve us?

If you believe that your very existence is tied to a functioning body you would surely live your life differently than if you were certain that whoever you were would continue to exist uninjured after the death of your body. If you believed that your existence ended with your death, how would you live? Hoarding things and experiences and maximizing pleasure would be the most logical thing to do. How likely is it that you will be ever completely satisfied if you knew you only had a limited amount of time to live?

Many schools of religious thought profess the existence of a transcendent soul or spirit that lives after the death of the body, but what kind of world are we living in today? Which paradigm are we actually subscribing to?

When the anesthetic gas is eliminated from the body consciousness returns on its own. Waking someone up simply requires enough space and time for it to occur spontaneously. There is no reversal agent available to speed the return of consciousness. The time required to emerge from anesthesia is directly related to the amount of time the patient has been exposed to the anesthetic. At some point the patient will open their eyes when a threshold has been crossed. Depending on how long the patient has been anesthetized, complete elimination of the agent from the body may not happen until a long while after the patient has “woke”.

By the time the patient arrives in the recovery room, they are safely on a path to their baseline state of awareness. Getting back to a normal state of awareness may take hours or even days. In some cases patients may never get their wits back completely. Neurocognitive testing has demonstrated that repeated exposure to general anesthesia can sometimes have long-lasting or even irreversible effects on the awake state. It may occur for everyone. Perhaps it is a matter of how closely we look.

Is fear keeping us “Anesthetized”?

Interestingly, it is well known that the long term effects of anesthetic exposure are more profound in individuals who have already been demonstrating elements of cognitive decline in their daily life. Indeed, this population of patients require significantly less anesthetic to reach the same depth of unconsciousness during an operation. This poses an intriguing question. Is our understanding of being awake also too simplistic? Is there a continuum of “awakeness” in everyday life just as there is one of unconsciousness when anesthetized? If so, how would we measure it?

Modern psychiatry has been rigorous in defining and categorizing dysfunction. Although there has been recent interest in pushing our understanding of what may be interpreted as a “super-functioning” psyche, western systems are still in their infancy with regard to this idea. In eastern schools of thought, however, this concept has been central for centuries.

In some schools of Eastern philosophy the idea of attaining a “super functioning” awake state is seen as something that also occurs spontaneously when intention and practice are oriented correctly. Ancient yogic scriptures specifically describe super abilities, or Siddhis, that are attained through dedicated practice. These Siddhis include fantastical abilities like levitation, telekinesis, dematerialization, remote-viewing and others. It is admittedly difficult for the Western mind to accept that a human being could ever do such things. We believe that a truly rational person would never entertain such fanciful ideas.

Being able to fly through the air or move material objects with thought aren’t the most potent of abilities available to the true adept in those traditions. In fact, these traditions regard these gifts (if they do exist) as very dangerous because they can easily distract the earnest seeker away from a greater potential. In these schools of thought the most advanced “superpowers” are those that allow a person to remain continuously in a state of joy and fearlessness, ideas that we are interestingly much more likely to accept as possible.

Are we too quick to assume that it is easier to be fearless than to “teleport” at will? Why would those traditions ascribe the most importance to fearlessness? Perhaps it has to do with the challenge of remaining in that state and the benefits of doing so. Note that If such a state were possible, it would be incompatible with the kind of absolute, psychological identification most of us have with our mortal bodies. It may be of no surprise that Eastern medicine subscribes to an entirely different perspective of the body and uses different tools to examine it.

Fear has served our ancestors well, helping us to avoid snakes and lions, but how much fear is necessary these days? Could fear be the barrier that separates us from our highest potential in the awake state just as an anesthetic gas prevents us from waking in the operating room? It is not possible to remain fearless while continuing to identify with a body that is prone to disease and death. Even if one were to drop the assumption that the source of our existence is a finite body, how long would it take to be free from the effects of a lifetime of fearful thinking before an individual outwardly manifests changes that reflect a shift in this paradigm? Is it possible that by continuing to leave this model unchallenged we never feel what it is like to be truly awake?

Putting fantastical abilities aside, can we predict what our world would look like if everyone lived joyfully and fearlessly without the desperate need to maximize pleasure and time? We can postulate that it would be better.

Our failure to identify the mechanism of anesthetic gasses may be a clue that we have been entirely misconceiving who we really are. Moreover, we have testimony from those who have actually died (by our clinical standards) and returned to tell us that we are worrying about the wrong things. Recall that some who have had Near Death Experiences were not simply having a vivid dream borne of random electrical impulses in a brain in the last throes of life; they were able to recount the details of the “failed” resuscitative efforts of those around them. It seems only logical to accept the paradigm that we are more than our bodies and enjoy the individual and societal benefits of this shift. Why are we so reluctant to adopt this perspective? Are we biased and if so, why?

The Possibility and Implications of Reincarnation

NDEs are not the only wrinkle in our paradigm of life, death and awareness. NDEs suggest that there could be a small part of us that transcends an event which we all call death, an undeniable and terminal event of a physical existence. In that sense, our physical bodies should be more aptly considered a small and temporary part of our real, transcendent nature. If that were the case, where then do “we” go after our bodies die? The answer may not be as faith-based or speculative as you think.

Let us, for a moment, take a step back from religious doctrine and agnosticism. These two perspectives represent a stark contrast in their approach to the question. One proclaims that the answer is unambiguously dictated in associated “scripture”. The other insists that the answer can not be known, at least for the moment.

Is there physical evidence that points to a different answer? There is not. We are dealing with a potential aspect of reality that transcends materialism, the philosophical doctrine that nothing exists outside matter and its actions upon itself. We may not have the evidence which our scientific system demands, but just as with NDEs, there is an awful lot of anecdotal evidence that may not be getting the attention it deserves.

Dr. Ian Stevenson was a physician and professor of psychiatry at the University of Virginia School of Medicine for 50 years. He served as the Chair of Psychiatry for ten of them. He is best known for his research into the study of reincarnation. During the course of his career he assiduously compiled over three thousand case studies of individuals who reported living on this planet as a different person prior to their current life.

What is fascinating about these cases is that the subjects are not adults that claim they were Pharaohs or Knights that served King Arthur in a “past” life. The subjects are children who caught the attention of their families when they were very young. They would insist that they had lived rather average lives before, had families of their own and recalled their previous name, details and location of their previous home and occasionally, the circumstances around their death. Often they would go ignored for some time but their dogged refusal to recant their peculiar tales was a matter of some curiosity to their families.

The fascinating part of every case in Stevenson’s data is that the child’s parents or others familiar with their story eventually stumbled across convincing evidence that the person the child claimed to have “embodied” in a previous life actually lived and died before their birth. Dr. Stevenson would attempt to authenticate the child’s account through interviews with the surviving members of the family of the deceased person the child claimed to have been. Sometimes extremely specific details of the previous life were confirmed, such as secrets that were kept between their old self and their spouse or physical details of their previous home that would only be known to those who lived there. When the child was “reunited” with the family of the deceased they could identify many of those in their old family, and pick out the imposters that Stevenson had planted to test the specificity of their recall.

Dr. Stevenson was an author of nearly three hundred papers and 14 books on reincarnation. In 1997 he authored a two volume tome of over two thousand pages titled Reincarnation in Biology that documented the stories of a subset 225 subjects that not only had specific recall of their past identities that matched those of real, deceased individuals but also had birthmarks or physical anomalies that corresponded to the manner of death of their previous “selves”.

For example, a child who recalled dying from a gunshot wound in a previous life was born with birthmarks that corresponded to the entry and exit wound of the bullet that purportedly killed that person. If accepted, this phenomenon can be considered more indirect evidence suggesting that our consciousness, which represents our transcendent nature, gives rise to our physical form and not the other way around. This fits nicely with our observations of patients under anesthesia while confirming that our consciousness is the product of a functioning body is no more than an assumption.

Let us take one of Dr. Stevenson’s more well known cases, that of Swarnlata Mishra who was born in India in 1948. At the age of three she began telling her parents of her previous life as a wife and mother of two in a different town in the same part of India. Her father was curious and accepting of these tales and began to take notes on everything her daughter uttered about her “past life” lived by a woman named Biya Pathak.

She recalled that her family owned an automobile which was quite rare at the time. She remembered the name of the doctor that treated her for what proved to be the cause of her death. She was also able to describe the details and relative location of the house in which she lived, as well as odd details like the fact that she had a few gold teeth. When she was ten, her story caught the attention of a researcher of paranormal studies in the area, professor Sri H.S. Banerjee, who was a colleague of Dr. Stevenson. He was able to locate the family of the girl’s previous life using the notes her father had taken and confirmed the details Swarnlata gave of Biya Pathak.

Swarnlata’s alleged previous family finally came to visit her. The two families did not know each other. She was able to easily identify her family members and detect the imposter that posed as one of her sons. She convinced her husband that she was once married to him by recounting an incident when she discovered he had taken a sum of money from a box that she kept. No other soul was aware of this secret.

Stevenson’s work has been criticized by some who felt his approach to validating these accounts were not rigorous and regarded his work as biased and unscientific. Others in the scientific community have defended his methodology and conclusions. Internationally recognized physicist Dr. Doris Kuhlmann-Wilsdorf has stated that based on his findings it is reasonable to conclude that there is an overwhelming possibility that reincarnation is in fact occurring. His work has been covered by Scientific American and The Washington Post.

Why would some scientists dismiss his “evidence” and others defend it? This is where we must be very careful in our own analysis. It is very easy to conclude that because someone has taken issue with his methodology we can shrug our shoulders and dismiss all of his findings en bloc and move on. If we choose to do that, are we being objective or are we protecting a belief system that we refuse to surrender?

It is also just as easy to proclaim there is finally proof of an idea that we hold dear. For the agnostics among us, this controversy is more evidence that the answer is beyond our grasp. Is it possible to be objective about this? Perhaps not. We are dealing with anecdotal evidence, not hard physical proof.

The point here is that it is wiser to acknowledge that certainty is clearly out of reach. Moreover, there is ample anecdotal evidence of exceptions to the tenet that our properly functioning physical bodies are solely responsible for consciousness. We should be able to agree that a rule with exceptions is only a partial explanation of what is really going on.

Will we ever find the Proof we are looking for?

Dr. Stevenson continued to admit that until a mechanism by which reincarnation can be explained could be identified it would remain a matter of speculation. That is a sentiment of a researcher that acknowledges the uncertainty behind his conclusions. Yet it also invites us to ask what sort of mechanism would we be able to identify to explain a phenomenon that transcends materialism. Are we ever going to be able to “prove” that reincarnation is taking place? If not, what are the implications of plodding along assuming that it isn’t?

The discussion of patients under anesthesia does not prove that our consciousness remains intact and continuous (though inaccessible retrospectively), however it does point out that this matter is far from resolved. Specifically it introduces the inescapable fact that we are not going to find the proof we are looking for in places we are looking for it.

Consciousness seems to transcend molecules, the very things we examine when looking for proof.

What are we to make of the results of Dr. Stevenson’s lifetime of investigation? Reincarnation, if it were happening, further supports the theory that death is not the end. More importantly, it should give us another reason to pause. Not only would it force us to reconsider our understanding of death, it also invites us to once again reassess how we should be living.

Would we change our behavior if we knew we were coming back to this planet for another go at it? What kind of choices would we make if we knew we would suffer the consequences or enjoy the benefits of our decisions made today in another lifetime? What kinds of decisions would we make collectively if we all subscribed to the idea that our actions in this lifetime were tied to the fate of our planet and species long after we “perished”? Given the fact that there is uncertainty surrounding this possible phenomenon, is it wiser to assume that he is wrong or right?

Are we biased?

We are now considering a real dilemma, not one based in hypotheticals or history where “the truth” has been dictated to us or revealed over the years. We basically have two paradigms to choose from. On the one hand there is no proof that our existence doesn’t continue after the death of our bodies. There also is ample indirect evidence that there is more to this life than this material body. We have the accounts of hundreds of people who have died, by our own standards of death, and returned to tell us we have been wrong about the whole thing.

Furthermore the idea that there are others who have died and have been reborn on this planet may not just be a fringe belief or part of Eastern religious doctrines. The evidence, if we were to accept it as such, is not being proclaimed by religious leaders or established scientific institutions. It’s coming “from the mouths of babes” from all over the world.

On the other hand, we are living in a world where just about everybody behaves in a manner that supports the belief that we each have a limited and finite existence. It is true that many humans believe in an after-life, or at least profess that they do, however that is not the way they behave. The point here is that even if you do believe you are a “transcendent” being, how feasible is it to act in that manner while interacting with a society full of people who are trying to outmaneuver you for a bigger piece of the pie? From a purely practical standpoint it is more sensible to play their game and protect and maximize what you have today so that you won’t be left with little tomorrow. In this sense, we really don’t have much of a choice in the matter as individuals. We are instead being pressured to assume a competitive posture because of our collective behavior as a society.

Bias, if it does exist in our minds, will emerge when we instead answer the question, “Are we as individuals and a society exaggerating a self-serving and fear-based narrative?”. This line of inquiry leads us to assess the nature of the information we receive on a regular basis. Are we commonly exposed to stories of cooperation, moderation and tolerance? Or are we more often exposed to tragedy, fear and the stories of those whose successes are measured in wealth, fame and youthfulness? How does our media characterize those who eschew the pursuit of material things for internal balance and harmony compared to those who have outwitted or outshined their fellow human beings and ended up with more?

Before we indict the media and the entertainment industry we would be better served by asking ourselves why we are more interested in these narratives to begin with. After all, if we weren’t intrigued by these kinds of stories there would be little incentive for them to create content along these lines.

I contend that our fascination with this kind of entertainment and news is inextricably tied to our level of understanding of the nature of who we really are. More importantly, the stories we are drawn to reinforce the belief that we have only one shot at happiness and a “winner take all” attitude is not just excusable but necessary. In this sense, the adversarial relationship we have with each other as individuals or societies gets perpetuated and simultaneously attributed to immutable “human nature”.

Is this truly our nature or are we missing something very big about ourselves? Moreover, are we constructing this idea of reality ourselves or are we being “nurtured” into doing so? Are we forcibly but insidiously being kept in a different kind of Dark Age? If so, what would be the motive in constructing that kind of reality and who would benefit from this? Whether or not there are unseen forces that perpetuate the idea that we are all in competition with each other we can say that a population that is not afraid to die is much harder to control.

Great article, I couldn't help but think of the documentary about David Bohm I recently watched

https://www.infinitepotential.com/

“The essential quality of the infinite is its subtlety, its intangibility. This quality is conveyed in the word spirit, whose root meaning is ‘wind or breath.’ That which is truly alive is the energy of spirit, and this is never born and never dies.”

– David Bohm

David Bohm stated, There exists a hidden regime of reality where everything is interconnected, no person can access that domain, mystical traditions teach us, we must be humble in front of reality, that there will always be domains of reality that will remain beyond science.

If the self were really there, then perhaps it would be correct to centre on the self because the self would be important. But if the self is a kind of illusion, at least the self as we know it, then to centre our thought on something illusory which is assumed to have importance is going to disrupt the whole PROCESS and it will not only make thought about yourself wrong, it will make thought about everything wrong so that it becomes a dangerous and destructive instrument all around.

Yes, who would we be and how different would our world be if we lived the truth that we are spiritual beings having a material experience.?